Two Musts for the Karloff Collector

Master Seminar

There have been numerous books about Boris Karloff and his films, several of them quite good. But the indispensable volume is Scott Allen Nollen’s Boris Karloff: A Critical Account of His Screen, Stage, Radio, Television, and Recording Work (McFarland, 473 pages, $48.50).

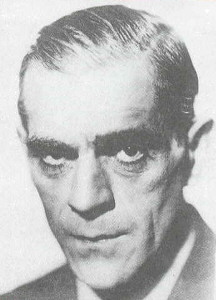

Nolan starts with a chapter on the personal life of William Henry Pratt (1887-1969), AKA Boris Karloff, showing how a black sheep actor from a family of British civil servants, after 20 years of character-actor obscurity on stage and screen, became, at 44, a superstar, one of the few actors billed simply by the last name. There were Garbo—and Dietrich—and Karloff the Uncanny. Nolan then turns to Karloff’s work, making at least passing mention of most of his 160+ films while focusing in detail on his contributions to horror cinema.

Nolan starts with a chapter on the personal life of William Henry Pratt (1887-1969), AKA Boris Karloff, showing how a black sheep actor from a family of British civil servants, after 20 years of character-actor obscurity on stage and screen, became, at 44, a superstar, one of the few actors billed simply by the last name. There were Garbo—and Dietrich—and Karloff the Uncanny. Nolan then turns to Karloff’s work, making at least passing mention of most of his 160+ films while focusing in detail on his contributions to horror cinema.

Nolan is at pains to point out that film is a collaborative medium, resisting the auteur theory that a film is the sole product of one person. He notes the vital role played in Karloff’s major films by such directors as James Whale, Karl Freund, and Edgar G. Ulmer, producer Val Lewton, and latter-day directors Dennis Day and Peter Bogdanovich. Nolan notes the important work of scriptwriters, photographers, composers, and master makeup artist Jack P. Pierce. At the same time, Nolan acknowledges that his book is a type of auteur study—‘star as auteur,’ as it were.

Indeed, the book provides ample evidence that Karloff, more than any other one person, be they director, actor, writer, or producer, formed the shape and direction of the classic horror film through his personal philosophy, his persona, and his unflagging professionalism.

Nolan’s approach to the films is refreshingly eclectic. While he makes use of many critical theories and approaches, he is prisoner to none of them, talking about how the films were made, evaluating performances, making reference to influential works of literature and then-current social trends, discussing both the films’ philosophical observations and aesthetic composition. Nolan’s concern is not to prove how clever a theorist he is, but simply to help us see the films better.

It’s pure pleasure to walk with Nolan through such acknowledged horror classics as Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Mummy, The Black Cat, The Body Snatcher, and Targets. He also casts light on such fine lesser-known films as The Black Room, The Walking Dead, and Corridors of Blood, and offers the first detailed consideration of the four Columbia “mad doctor” films. He also casts a wider genre net, with chapters on “Historical Horror: Tower of London,” “Gangster Horror: Black Friday” and “Political Horror: Devil’s Island.”

I can’t fault what he’s done; I can only hunger for even more. It would be good to have more than 11 pages on Karloff’s more than 75 pre-Frankenstein films. It would be nice to have a five-page chapter, rather than just a page, on Karloff’s mainstream appearances in The Lost Patrol and House of Rothschild. Dick Tracy Meets Gruesome, a better film than the title suggests, deserves more than a passing mention, as does the “Mr. Wong” series. And I’ve yet to find a critic who likes Night Key half as well as it deserves.

More to the point, Nolan’s approach to Karloff’s performances in non-film media, while intelligent and touching the major bases, is comparatively brief. (Though it must be added that the book contains a complete filmography, complete lists of television appearances, audio-recordings, and Karloff’s published writings, and a representative sampling of his stage and radio appearances.) Here’s hoping that some reader of this review is inspired to fill a major gap by writing a book about Karloff’s major 20-year contribution to television.

But this is one of those books that is not just good, but good beyond hope. It belongs in the library of everyone who cares about classic horror, and/or first-rate acting.

Crisscross Terror

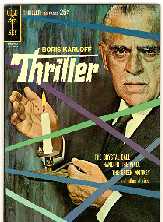

The Golden Age of horror/suspense/science fiction anthology television rose in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, a period that saw, among others, One Step Beyond (1959-1961), The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1959-1962), The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (1962-1965), The Outer Limits (1963-1965)—and Thriller (1960-1962).

The Golden Age of horror/suspense/science fiction anthology television rose in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, a period that saw, among others, One Step Beyond (1959-1961), The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1959-1962), The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (1962-1965), The Outer Limits (1963-1965)—and Thriller (1960-1962).

Thriller episodes opened with an introduction by Boris Karloff, followed by Pete Rugolo’s jangling theme music, and the white crisscross pattern (by Jerome Gould) that was its logo. In This is a Thriller: An Episode Guide, History and Analysis of the Classic 1960s Television Series (McFarland, 207 pages, $45) Alan Warren suggests that “crisscrossing” was what the series was about.

Executive Producer Hubbell Robinson conceived the show as “a quality anthology drawing on the whole rich field of suspense literature,” and hired Karloff as host. Working from Robinson’s vague description, the first producer churned out seven episodes that felt like second-rate Hitchcock knock-offs. To save the series, Robinson then defined Thriller as being either crime or horror, and hired two new producers. Maxwell Shane took over the “crime” part, producing some outstanding episodes and some mediocre ones. William Frye, assigned to make the “horror” episodes, ended up producing the majority of the shows and giving the series its distinctive flavor.

The “schizophrenic” alternation between crime and horror confused, and confuses, some viewers. This was compounded by the fact that a number of episodes combined crime and horror elements. but for the open-minded viewer this crisscrossing gives Thriller a unique feel. From episode to episode, one doesn’t know whether the reolution will prove to be natural or supernatural.

Thriller used stories from Weird Tales and other pulp magazines written by authors such as Robert E. Howard, Cornell Woolrich, and Robert Bloch. It employed talented scriptwriters, notably Bloch and John S. Sanford; talented directors, including Ida Lupino and One Step Beyond’s host/director, John Newland; gifted composers (Martin Stevens and Jerry Goldsmith); and talented actors, both veterans (John Carradine, Henry Daniell, Mary Astor, and of course Karloff) and up-and-coming (Richard Chamberlain, William Shatner, Mary Tyler Moore).

Warren’s slender volume is remarkably dense with information. Following a chapter on the show’s history, he gives a guide to all 67 episodes, including plot summaries, biographies of writers, casts, and crew, and critical evaluations. While clearly devoted to the series, Warren is unsparingly honest about its defects. The one episode I was able to view recently struck me as a solid, entertaining programmer, yet Warren judges it below average, suggesting that the episodes he hails as classics or near classics are very good indeed.

Warren concludes with short looks at the “Ancestors” and “Descendants” of Thriller, and a list of the 25 episodes most requested by members of the Thriller fan club. This book is a model for how series guides should be done.

* * *

You can learn more about Thriller, and order episodes, from Ken Kaffke’s The Thriller Club.